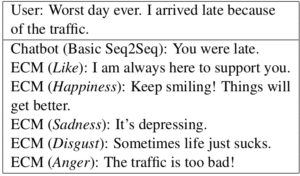

Is this a breakthrough in robot emotion? Zhou et al describe the Emotional Chatting Machine (ECM), a chatbot which uses machine learning to return answers with a specified emotional tone.

Is this a breakthrough in robot emotion? Zhou et al describe the Emotional Chatting Machine (ECM), a chatbot which uses machine learning to return answers with a specified emotional tone.

The ultimate goal of such bots is to produce a machine that can detect the emotional tone of an input and choose the optimum tone for its response, but this is very challenging. It’s not simply a matter of echoing the emotional tone of the input; the authors suggest for example, that sympathy is not always the appropriate response to a sad story. For now, the task they address is to take two inputs; the actual content and a prescribed emotional tone, and generate a response to the content reflecting the required tone. Actually, doing more than reflecting is going to be very challenging indeed because the correct tone of a response ought to reflect the content as well as the tone of the input; if someone calmly tells you they’re about to die, or about to kill someone else, an equally calm response may not be emotionally appropriate (or it could be in certain contexts; this stuff is, to put it mildly, complex).

To train the ECM, two databases were used. The NLPCC dataset has 23,105 sentences collected from Weibo, a Chinese blog site, and categorised by human beings using eight categories: Anger, Disgust, Fear, Happiness, Like, Sadness, Surprise and Other. Fear and Surprise turned up too rarely on Weibo blogs to be usable in practice.

Rather than using the NLPCC dataset directly, the researchers used it to train a classifier which then categorised the larger STC dataset, which has 219,905 posts and 4,308,211 responses; they reckon they achieved an accuracy of 0.623, which doesn’t sound all that great, but was apparently good enough to work with; obviously this is something that could be improved in future. It was the ’emotionalised’ STC data set which was then used to train the ECM for its task.

Results were assessed by human beings for both naturalness (how human they seemed) and emotional accuracy; ECM improved substantially on other approaches and generally turned in a good performance, especially on emotional accuracy. Alas, the chattbot is not available to try out online.

This is encouraging but I have a number of reservations. The first is about the very idea of an emotional chatbot. Chatbots are almost by definition superficial. They don’t attempt to reproduce or even model the processes of thought that underpin real conversation, and similarly they don’t attempt to endow machines with real or even imitation emotion (the ECM has internal and external memory in which to record emotional states, but that’s as far as it goes). Their performance is always, therefore, on the level of a clever trick.

Now that may not matter, since the aim is merely to provide machines that deal better with emotional human beings. They might be able to do that without having anything like real or even model emotions themselves (we can debate the ethical implications of ‘deceiving’ human interlocutors like this another time). But there must be a worry that performance will be unreliable.

Of course, we’ve seen that by using large data sets, machines can achieve passable translations without ever addressing meanings; it is likely enough that they can achieve decent emotional results in the same sort of way without ever simulating emotions in themselves. In fact the complexity of emotional responses may make humans more forgiving than they are for translations, since an emotional response which is slightly off can always be attributed to the bot’s personality, mood, or other background factors. On the other hand, a really bad emotional misreading can be catastrophic, and the chatbot approach can never eliminate such misreading altogether.

My second reservation is about the categorisation adopted. The eight categories adopted for the NLPCC data set, and inherited here with some omissions, seem to belong to a family of categorisations which derive ultimately from the six-part one devised by Paul Ekman: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. The problem with this categorisation is that it doesn’t look plausibly comprehensive or systematic. Happiness and sadness look like a pair, but there’s no comparable positive counterpart of disgust or fear, for example. These problems have meant that the categories are often fiddled with. I conjecture that ‘like’ was added to the NLPCC set as a counterpart to disgust, and ‘other’ to ensure that everything could be categorised somewhere. You may remember that n the Pixar film Inside Out Surprise didn’t make the cut; some researchers have suggested that only four categories are really solid, with fear/surprise and anger/disgust forming pairs that are not clearly distinct.

The thing is, all these categorisations are rooted in attempts to categorise facial expressions. It isn’t the case that we necessarily have a distinct facial expression for every possible emotions, so that gives us an incomplete and slightly arbitrary list. It might work for a bot that pulled faces, but one that provides written outputs needs something better. I think a dimensional approach is better; one that defines emotions in terms of a few basic qualities set out along different axes. These might be things like attracted/repelled, active/passive, ingoing/outgoing or whatever. There are many models along these lines and they have a long history in psychology; they offer better assurance of a comprehensive account and a more hopeful prospect of a reductive explanation.

I suppose you also have to ask whether we want bots that respond emotionally. The introduction of cash machines reduced the banks’ staff costs, but I believe they were also popular because you could get your money without having to smile and talk. I suspect that in a similar way we really just want bots to deliver the goods (often literally), and their lack of messy humanity is their strongest selling point. I suspect though, that in this respect we ain’t seen nothing yet…

I was interested to see this Wired

I was interested to see this Wired  Ah, the oft-promised passing of the Turing Test. Wake me up when it happens – we’ve been round this course so many times in the past.

Ah, the oft-promised passing of the Turing Test. Wake me up when it happens – we’ve been round this course so many times in the past.