Adam Pautz has a new argument to show that consciousness is irreducible (that is, it can’t be analysed down into other terms like physics or functions). It’s a relatively technical paper – a book length treatment is forthcoming, it seems – but at its core is a novel variant on the good old story of Mary the Colour Scientist. Pautz provides several examples in support of his thesis, and I won’t address them all, but a look at this new Mary seems interesting.

Adam Pautz has a new argument to show that consciousness is irreducible (that is, it can’t be analysed down into other terms like physics or functions). It’s a relatively technical paper – a book length treatment is forthcoming, it seems – but at its core is a novel variant on the good old story of Mary the Colour Scientist. Pautz provides several examples in support of his thesis, and I won’t address them all, but a look at this new Mary seems interesting.

Pautz begins by setting out a generalised version of how plausible reductive accounts must go. His route goes over some worrying territory – he is quite Russellian, and he seems to take for granted the old and questionable distinction between primary and secondary qualities. However, if the journey goes through some uncomfortable places, the destination seems to be a reasonable place to be. This is a moderately externalist kind of reduction which takes consciousness of things to involve a tracking relation to qualities of real things out there. We need not worry about what kinds of qualities they are for current purposes, and primary and secondary qualities must be treated in a similar way. Pautz thinks that if he can show that reductions like this are problematic, that amounts to a pretty good case for irreducibility.

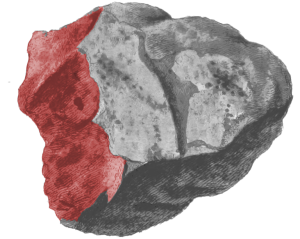

So in Pautz’s version, Mary lives on a planet where the outer surfaces of everything are black, grey, or white. However, on the inside they are brilliantly coloured, with red, reddish orange, and green respectively. All the things that are black outside are red inside, and so on, and this is guaranteed by a miracle ‘chemical’ process such that changes to the exterior colour are instantly reflected in appropriate changes inside. Mary only sees the outsides of things, so she has never seen any colours but black, white and grey.

Now Mary’s experience of black is a tracking relation to black reflectances, but in this world it also tracks red interiors. So does she experience both colours? If not, then which? A sensible reductionist will surely say that she only experiences the external colour, and they will probably be inclined to refine their definitions a little so that the required tracking relation requires an immediate causal connection, not one mediated through the oddly fixed connection of interior and exterior colours. But that by no means solves the problem, according to Pautz. Mary’s relation to red is only very slightly different to her relation to black. Similar relations ought to show some similarity, but in this case Mary’s relation to black is a colour experience, whereas her relation to red, intrinsically similar, is not a colour experience – or an experience of any kind! If we imagine Martha in another world experiencing a stone with a red exterior, then Martha’s relation to red and Mary’s are virtually identical, but have no similarity whatever. Suppose you had a headache this morning, suggests Pautz, could you then say that you were in a nearly identical state this afternoon, but that it was not the state of experiencing a headache; in fact it was no experience at all (not even, presumably, the experience of not having a headache).

Pautz thinks that examples of this kind show that reductive accounts of consciousness cannot really work, and we must therefore settle for non-reductive ones. But he is left offering no real explanation of the relation of being conscious of something; we really have to take that as primitive, something just given as fundamental. Here I can’t help but sympathise with the reductionists; at least they’re trying! Yes, no doubt there are places where explanation has to stop, but here?

What about Mary? The thing that troubles me most is that remarkable chemical connection that guarantees the internal redness of things that are externally black. Now if this were a fundamental law of nature, or even some logical principle, I think we might be willing to say that Mary does experience red – she just doesn’t know yet (perhaps can never know?) that that’s what black looks like on the inside. If the connection is a matter of chance, or even guaranteed by this strange local chemistry, I’m not sure the similarity of the tracking relations is as great as Pautz wants it to be. What if someone holds up for me a series of cards with English words on one side? On the other, they invariably write the Spanish equivalent. My tracking relation to the two words is very similar, isn’t it, in much the same way as above? So is it plausible to say I know what the English word is, but that my relation to the Spanish word is not that of knowing it – that in fact that relation involves no knowledge of any kind? I have to say I think that is perfectly plausible.

I can’t claim these partial objections refute all of Pautz’s examples, but I’m keeping the possibility of reductive explanations open for now.

Sam Coleman returned in a recent paper (JCS vol 16, n0 2-3) to the old perennial of

Sam Coleman returned in a recent paper (JCS vol 16, n0 2-3) to the old perennial of