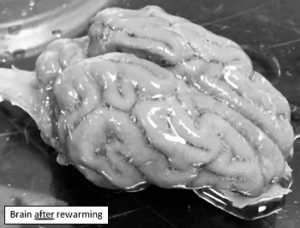

The prize offered by the Brain Preservation Foundation has been won by 21st Century Medicine (21CM) with the Aldehyde-Stabilized Cryopreservation (ASC) technique that has been developed. In essence this combines chemical and cryogenic approaches and is apparently capable of preserving the whole connectome (or neural network) of a large mammalian brain (a pig brain here) in full detail and indefinitely. That is a remarkable achievement. A paper is here.

The prize offered by the Brain Preservation Foundation has been won by 21st Century Medicine (21CM) with the Aldehyde-Stabilized Cryopreservation (ASC) technique that has been developed. In essence this combines chemical and cryogenic approaches and is apparently capable of preserving the whole connectome (or neural network) of a large mammalian brain (a pig brain here) in full detail and indefinitely. That is a remarkable achievement. A paper is here.

I am an advisor to the BPF, though I should make it clear that they don’t pay me and I haven’t given them a great deal of advice. I’ve always said I would be a critical friend, in that I doubt this research is ever going to lead to personal survival of the self whose brain is preserved. However, in my opinion it is much more realistic than a pure scan-and-upload approach, and has the potential to yield many interesting benefits even if it never yields personal immortality.

One great advantage of preserving the brain like this is that it defers some choices. When we model a brain or attempt to scan it into software, we have to pick out the features we think are salient, and concentrate on those. Since we don’t yet have any comprehensive and certain account of how the brain functions, we might easily be missing something essential. If we keep the whole of an actual brain, we don’t have to make such detailed choices and have a better chance of preserving features whose importance we haven’t yet recognised.

It’s still possible that we might lose something essential, of course. ASC, not unreasonably, concentrates on preserving the connectome. I’m not sure whether, for example, it also keeps the brain’s astrocytes in good condition, though I’d guess it probably does. These are the non-neural cells which have often been regarded as mere packing, but which may in fact have significant roles to play. Recently we’ve heard that neurons appear to signal with RNA packets; again, I don’t know whether ASC preserves any information about that – though it might. But even on a pessimistic view, ASC must in my view be a far better preservation proposition than digital models that explicitly drop the detailed structure of individual neurons in favour of an unrealistically standardised model, and struggle with many other features.

Preserving brains in fine detail is a worthy project in itself, which might yield big benefits to research in due course. But of course the project embodies the hope that the contents of a mind and even the personality of an individual could be delivered to posterity. I do not think the contents of a mind are likely to be recoverable from a preserved brain yet awhile, but in the long run, why not? On identity, I am a believer in brute physical continuity. We are our brains, I believe (I wave my hands to indicate various caveats and qualifications which need not sideline us here). If we want to retain our personal identity, then, the actual physical preservation of the brain is essential.

Now, once your brain has been preserved by ASC, it really isn’t going to be started up again in its existing physical form. The Foundation looks to uploading at this stage, but because I don’t think digital uploading as we now envision it is possible in principle, I don’t see that ever working. However, there is a tiny chink of light at the end of that gloomy tunnel. My main problem is with the computational nature of uploading as currently envisaged. It is conceivable that the future will bring non-computational technologies which just might allow us to upload, not ourselves, but a kind of mental twin at least. That’s a remote speculation, but still a fascinating prospect. Is it just conceivable that ways might be found to go that little bit further and deliver some kind of actual physical interaction between these hypothetical machines and the essential slivers of a preserved brain, some echo such that identity was preserved? Honestly, I think not, but I won’t quite say it is inconceivable. You could say that in my view the huge advantage of the brain preservation strategy for achieving immortality is that unlike its rivals it falls just short of being impossible in principle.

So I suppose, to paraphrase Gimli the dwarf: certainty of death; microscopic chance of success – what are we waiting for?

Postscript: I meant by that last bit that we should continue research, but I see it is open to misinterpretation. I didn’t dream people would actually do this, but I read that Robert McIntyre, lead author of the paper linked above, is floating a startup to apply the technique to people who are not yet dead. That would surely be unethical. If suicide were legal and if you had decided that was your preferred option, you might reasonably choose a method with a tiny chance of being revived in future. But I don’t think you can ask people to pay for a technique (surely still inadequately tested and developed for human beings) where the prospects of revival are currently negligible and most likely will remain so.

A digital afterlife is likely to be available one day, according to Michael Graziano, albeit not for some time; his

A digital afterlife is likely to be available one day, according to Michael Graziano, albeit not for some time; his