Gregg Rosenberg’s book “A Place for Consciousness – probing the deep structure of the natural world ” is the most ambitious metaphysical project I have come across for a long time. Not only does it offer a new view of consciousness, it suggests a new and elaborate theory of causality, and a new kind of ontology to go with it. It pushes metaphysical speculation boldly into regions which science has pretty much regarded as its own for many years, and brusquely denies the completeness of the physical account. It also embraces philosophical positions which most would regard as untenable: in this, it recalls David Chalmers, and indeed Rosenberg positions himself as operating in a kind of post-Chalmers context with some Chalmerian (Chelmersian?) leanings.

Gregg Rosenberg’s book “A Place for Consciousness – probing the deep structure of the natural world ” is the most ambitious metaphysical project I have come across for a long time. Not only does it offer a new view of consciousness, it suggests a new and elaborate theory of causality, and a new kind of ontology to go with it. It pushes metaphysical speculation boldly into regions which science has pretty much regarded as its own for many years, and brusquely denies the completeness of the physical account. It also embraces philosophical positions which most would regard as untenable: in this, it recalls David Chalmers, and indeed Rosenberg positions himself as operating in a kind of post-Chalmers context with some Chalmerian (Chelmersian?) leanings.

A breath of fresh air, then? I think so, though I couldn’t sign up unreservedly to the theory, and I have particular reservations about the elaborate apparatus which Rosenberg proposes to deal with causality.

Anyway, what’s it all about? The basis of the theory is the view that conscious experience – qualia in particular – cannot be satisfactorily accommodated within the physicalist account. Rosenberg proposes an analogy with Conway’s “Game of Life”. In this game, we have a world consisting of an indefinitely large grid. Each cell can be “off” or “on”. Some simple rules about adjacent cells determine, for each successive state of the world, which cells will be on or off. It turns out that this simple set-up gives rise to patterns which evolve and behave in complex and interesting ways. We can even construct a huge pattern which acts as a Turing machine.

Now, says Rosenberg, in the Life world, there is nothing but bare differences. You may be able to generate hugely complex entities within the Life world – perhaps even life itself: but there’s no way these bare differences could entail subjective experience. Yet subjective experience is undeniable – qualia are an observable fact. Now when you get right down to it, the world sketched out by physics is also a matter of bare differences. The fundamentals are a little more complex than in the Life world, but in the end you come down to a similar kind of contentless data. It follows that conscious experience is not entailed by physics, and it must therefore be entailed by something else.

The Game of Life is fascinating and instructive, but I think there’s a bit of trickery going on here. Rosenberg only ever talks about small sections of the Life world – of course you can’t do much with a grid the size of a chess board. He mentions the Turing machine, which requires a huge grid, of course, but even that is a minute fraction of the size of the array you’d need to model the full working detail of even one human brain. The Life grid needed for even a small community of people just beggars the imagination, and at that point it ceases to be convincing that the thing is too simple to support the kind of mental experience we normally have.

The Game of Life is fascinating and instructive, but I think there’s a bit of trickery going on here. Rosenberg only ever talks about small sections of the Life world – of course you can’t do much with a grid the size of a chess board. He mentions the Turing machine, which requires a huge grid, of course, but even that is a minute fraction of the size of the array you’d need to model the full working detail of even one human brain. The Life grid needed for even a small community of people just beggars the imagination, and at that point it ceases to be convincing that the thing is too simple to support the kind of mental experience we normally have.

At the end of the day, it’s just another appeal to intuition we’re dealing with here. Rosenberg insists that he’s giving real evidence, but if all you have for evidence is the way something looks to you, I say we’re just sharing intuitions, and mine are different from his.

I don’t like the argument much, either, but for different reasons. I see why you’re inclined to reject subjective evidence – “subjective” has always been a derogatory term in science. But if it’s the nature of phenomenal experience we’re dealing with, how can you disallow subjective evidence?

I don’t like the argument much, either, but for different reasons. I see why you’re inclined to reject subjective evidence – “subjective” has always been a derogatory term in science. But if it’s the nature of phenomenal experience we’re dealing with, how can you disallow subjective evidence?

Still, I don’t think it’s legitimate to argue that what’s true of a simple game must be true of reality, too. Life is a world only metaphorically; it seems doubtful to me that such a world is really possible (even in the required, fantastically outré, sense of the word “possible”). At least, if it’s to be real, there are going to be some problems about preserving identities between the successive, independent moments which constitute time in the game. And that’s one of the key points: the Life world is, by specification, a discrete-state world consisting of a binary grid. It is completely computational. The real world, by contrast, is messily continuous and full of non-computable stuff. This is particularly relevant because (according to me and many others) consciousness and qualia are among those non-computable features. Arguing from Life to reality just begs the question.

However, as a matter of fact, I think Rosenberg’s incredulity is justified. How can mere physical facts entail subjective experience?

It’s obvious that physical facts entail mental facts. Rosenberg chooses to defend his views with some very subtle and sophisticated argumentation about esoteric philosophical points, but we’re not dealing with esoteric matters here. A smack round the head with a spade is a physical fact, and entails plenty of consequences for your so-called “qualia”. Less brutally, having a red object stuck in front of my eyes in good lighting conditions entails an experience of redness in my mind. I know there’s plenty of scope for quibbling about the exact nature of the counterfactual conditionals and all that, but at the end of the day are you going to say there’s no entailment between the physical facts and mental experiences? That’s going to disconnect your experiences from the world altogether, isn’t it? You could take shelter in a restricted sense of “entailment”, but to his credit, Rosenberg quite rightly argues that we need to understand entailment in a broad sense here – certainly much wider than formal or logical entailment, anyway.

It’s obvious that physical facts entail mental facts. Rosenberg chooses to defend his views with some very subtle and sophisticated argumentation about esoteric philosophical points, but we’re not dealing with esoteric matters here. A smack round the head with a spade is a physical fact, and entails plenty of consequences for your so-called “qualia”. Less brutally, having a red object stuck in front of my eyes in good lighting conditions entails an experience of redness in my mind. I know there’s plenty of scope for quibbling about the exact nature of the counterfactual conditionals and all that, but at the end of the day are you going to say there’s no entailment between the physical facts and mental experiences? That’s going to disconnect your experiences from the world altogether, isn’t it? You could take shelter in a restricted sense of “entailment”, but to his credit, Rosenberg quite rightly argues that we need to understand entailment in a broad sense here – certainly much wider than formal or logical entailment, anyway.

But look – the last century or so has seen an accelerating accumulation of experimental results which show just how closely our mental life depends on the physical operation of our brain: yet none of this seems to have impinged on Rosenberg. He argues from a perspective that is almost medieval. We know better than that.

No, no! You talk as though he were arguing for dualism. Rosenberg isn’t trying to disconnect the physical and mental worlds: he’s just pointing out that there is more to be said about the world than the bare facts of physics. Remember this is pure physics we’re talking about. I think any unprejudiced observer, even a thorough materialist, would accept that there are aspects of the world which cannot be captured by talking about basic quantum physics. I realise some of the arguments are a bit sophisticated for your taste, but isn’t it true, as Rosenberg says, that if conscious experience were directly entailed by simple physics, it would be, in some sense, a free lunch? The idea of getting an additional phenomenal world for free in this sense really is hard to swallow, I think, and I find the argument on this persuasive.

No, no! You talk as though he were arguing for dualism. Rosenberg isn’t trying to disconnect the physical and mental worlds: he’s just pointing out that there is more to be said about the world than the bare facts of physics. Remember this is pure physics we’re talking about. I think any unprejudiced observer, even a thorough materialist, would accept that there are aspects of the world which cannot be captured by talking about basic quantum physics. I realise some of the arguments are a bit sophisticated for your taste, but isn’t it true, as Rosenberg says, that if conscious experience were directly entailed by simple physics, it would be, in some sense, a free lunch? The idea of getting an additional phenomenal world for free in this sense really is hard to swallow, I think, and I find the argument on this persuasive.

Anyway, the second stage of the argument is a consideration of panexperientialism. This is, if you like, a weaker version of panpsychism. It’s not that everything has a mind of its own, but rather that everything has a limited share of simple experience. Rosenberg distinguishes between the kind of full subjective experience human beings have, complex and infused with cognition, and the kind of tiny spark of subjectivity an inanimate particle might be thought to have. Ultimately, his theory sets out a way of building higher-level entities out of these tiny sparks.

There’s a curious use here of Ned Block’s Chinese Nation argument. Block proposed that each Chinese citizen could be set to reproducing the behaviour of single neuron in a brain: would the resulting higher-level entity really be conscious? (It has been pointed out that in fact the population of China is nothing like as large as the number of neurons in a human brain, and the example has an unfortunate racial tinge, especially taken in conjunction with Searle’s Chinese room argument.) Rosenberg says yes, and uses the argument to show that experiencing entities could exist on several levels. For reasons which are not completely clear to me, he regards this as a problem – if experience can happen at different levels, he feels the only logical stopping points are either consciousness as a property of every atom, or consciousness as a property only of the cosmos as a whole. He suggest that there is a “boundary problem” about why consciousness has the limits it does. The existence of consciousness at a middle level therefore needs explanation – but surely the argument actually shows that it could equally well exist at various levels? Rosenberg, of course, ultimately wants to offer an explanation of how low-level experience can be built up into higher-level structures.

Poor old Occam must be spinning in his grave at this point: but can I just spool the argument back for a moment? Rosenberg began by arguing that nothing like bare differences in the world could entail the fantasmagoria of subjective experience, right? But now – and only now – he starts to suggest that subjective experience might be made up of minute glints of experience. Now it seems to me that these tiny sparks of experience look a lot more like the kind of thing you might get from bare differences, and if Rosenberg had started with them his argument would have looked much less persuasive.

Poor old Occam must be spinning in his grave at this point: but can I just spool the argument back for a moment? Rosenberg began by arguing that nothing like bare differences in the world could entail the fantasmagoria of subjective experience, right? But now – and only now – he starts to suggest that subjective experience might be made up of minute glints of experience. Now it seems to me that these tiny sparks of experience look a lot more like the kind of thing you might get from bare differences, and if Rosenberg had started with them his argument would have looked much less persuasive.

There’s something a bit shifty about his discussion of panexperientialism, anyway. I’d like it a lot better if he came out thumping the table and declaring that panexperientialism is true, and here’s why. Instead, he sort of argues that there’s no reason why it couldn’t be true – maybe it’s even likely? The real reason he wants us to accept the plausibility of panexperientialism is that he wants it as the foundation for his theory, but in itself there are lots of reasons to dismiss it. One, of course, is that it adds an enormous number of experiencing entities to the world for no particular reason, and hence offends against parsimony – though parsimony doesn’t seem to be a principle Rosenberg values very much. Second, once again, we know quite well that the functional properties of the brain are closely associated with our ability to have experiences – even quite simple ones. A certain minimum of structure is necessary to have those functional qualities, and single particles certainly don’t have that minimum. Rosenberg argues against functionalism itself, but you don’t have to think that functional properties constitute consciousness in order to see that it depends on them.

I think it’s true that Rosenberg basically wants panexperientialism for the sake of the theory he builds on it, but why not? If the theory accounts for consciousness and causality, then it’s well worth it.

I think it’s true that Rosenberg basically wants panexperientialism for the sake of the theory he builds on it, but why not? If the theory accounts for consciousness and causality, then it’s well worth it.

The next step in the argument, in any case, is an assault on causality. Rosenberg launches an attack on what he characterises as Humean views. I have to say that Hume comes over here as a dogmatic figure rather at odds with the gently devastating agnostic I’m familiar with, but causality undoubtedly remains one of the great mysteries. Rosenberg wants us to unscramble some of our assumptions and stop thinking purely in terms of causal responsibility. He proposes the more general idea of causal significance, and wants to deal separately with effective and receptive causal properties. The physical account, he suggests, deals only with effective properties, and is hence one-sided.

Yes – according to him, we’re all talking about effective causal properties. Actually, I think that’s another mediaevalism, and most of us are not talking about causal properties at all – they sound worryingly vitalistic to me. In another place Rosenberg points out, more accurately, I think, that the account given by physics doesn’t actually make use of the concepts of cause and effect as such – it simply describes certain regularities in the space-time continuum. Now I think the normal view is to see cause and effect as simply a matter of an arbitrary cross-section or a line across this continuum. No particular line is privileged; it’s just a matter of what you happen to find salient or interesting at the time. The whole idea of “causal powers” is redundant. And then he goes on to say that receptive properties are connections? What does that mean? How can receptive causal properties be connections?

Yes – according to him, we’re all talking about effective causal properties. Actually, I think that’s another mediaevalism, and most of us are not talking about causal properties at all – they sound worryingly vitalistic to me. In another place Rosenberg points out, more accurately, I think, that the account given by physics doesn’t actually make use of the concepts of cause and effect as such – it simply describes certain regularities in the space-time continuum. Now I think the normal view is to see cause and effect as simply a matter of an arbitrary cross-section or a line across this continuum. No particular line is privileged; it’s just a matter of what you happen to find salient or interesting at the time. The whole idea of “causal powers” is redundant. And then he goes on to say that receptive properties are connections? What does that mean? How can receptive causal properties be connections?

That is really the key to the system. A simple model would have individual elements each with its own effective and receptive facets, but as I understand it, Rosenberg prefers to see receptive properties as properties which connect individual elements. The complexes so formed have both receptive and effective properties and constitute “natural individuals”. Causal relations between individuals and complexes help to impose constraints on the possible states of the component individuals, with the system tending towards higher levels of determinateness where possible. I must admit that the apparatus proposed here is rather complex and the motivation for some of the details is not always clear to me, so I might be misrepresenting the theory. It seems to be Rosenberg’s idea that phenomenal experience is the ultimate substrate or “carrier” of physics itself. Moreover, the concatenation of simple elements into higher level complexes eventually gives rise to true consciousness: the Consciousness Hypothesis tells us that “Each individual consciousness carries the nomic content of a cognitively structured, high-level natural individual. Conscious experience is experience of he total constraint structure active in the receptive field of an individual.”

That is really the key to the system. A simple model would have individual elements each with its own effective and receptive facets, but as I understand it, Rosenberg prefers to see receptive properties as properties which connect individual elements. The complexes so formed have both receptive and effective properties and constitute “natural individuals”. Causal relations between individuals and complexes help to impose constraints on the possible states of the component individuals, with the system tending towards higher levels of determinateness where possible. I must admit that the apparatus proposed here is rather complex and the motivation for some of the details is not always clear to me, so I might be misrepresenting the theory. It seems to be Rosenberg’s idea that phenomenal experience is the ultimate substrate or “carrier” of physics itself. Moreover, the concatenation of simple elements into higher level complexes eventually gives rise to true consciousness: the Consciousness Hypothesis tells us that “Each individual consciousness carries the nomic content of a cognitively structured, high-level natural individual. Conscious experience is experience of he total constraint structure active in the receptive field of an individual.”

Frankly, that seems to me just an over-developed and unduly obscure version of a Higher Order theory. Causation looks to me like a primitive – one of those basic concepts you can’t analyse. When you try to do it, the primitive keeps popping up in your explanation, reducing it to circularity. Don’t you think that happens here? These individuals which get grouped together – they are imposing constraints on each other, but doesn’t that mean they are causing each other to be one way and not another? Yet we are supposed to be below the level of cause and effect here – we’re meant to be explaining how causes work!

Frankly, that seems to me just an over-developed and unduly obscure version of a Higher Order theory. Causation looks to me like a primitive – one of those basic concepts you can’t analyse. When you try to do it, the primitive keeps popping up in your explanation, reducing it to circularity. Don’t you think that happens here? These individuals which get grouped together – they are imposing constraints on each other, but doesn’t that mean they are causing each other to be one way and not another? Yet we are supposed to be below the level of cause and effect here – we’re meant to be explaining how causes work!

The real killer is this. Rosenberg set out to explain qualia, but at the end of the day it seems to me your real qualophile would say: yes, that’s all very interesting, Gregg – thing is, I can imagine all of that happening without my actually experiencing the real redness of red. I don’t see anything in your theory which actually catches the vivid reality of subjective experience. Now of course, in my eyes all talk of qualia is so much hot air, but I don’t see why that would be any less plausible than the case for qualia was in the first place.

I think the impression of circularity arises from your using an unduly loose sense of “cause”, and I don’t see how anyone could read a theory about relations between subjective experiences without seeing how it relates to qualia.

I think the impression of circularity arises from your using an unduly loose sense of “cause”, and I don’t see how anyone could read a theory about relations between subjective experiences without seeing how it relates to qualia.

I don’t buy the theory completely myself, as a matter of fact, but to me it’s a very welcome piece of radical new thinking, and unlike some others, this is a book I intend to read again.

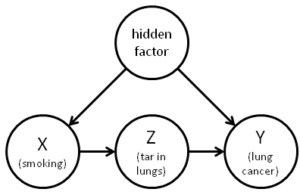

Judea Pearl says that AI needs to learn causality. Current approaches, even the fashionable machine learning techniques, summarise and transform, but do not interpret the data fed to them. They are not really all that different from techniques that have been in use since the early days.

Judea Pearl says that AI needs to learn causality. Current approaches, even the fashionable machine learning techniques, summarise and transform, but do not interpret the data fed to them. They are not really all that different from techniques that have been in use since the early days.

The older I get, the less impressed I am by the hardy perennial of free will versus determinism. It seems to me now like one of those completely specious arguments that the Sophists supposedly used to dumbfound their dimmer clients.

The older I get, the less impressed I am by the hardy perennial of free will versus determinism. It seems to me now like one of those completely specious arguments that the Sophists supposedly used to dumbfound their dimmer clients.