We are the alternate personalities of a cosmos suffering from Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). That’s the theory put forward by Bernardo Kastrup in a recent JCS paper and supported by others in Scientific American. I think there’s no denying the exciting elegance of the basic proposition, but in my view the problems are overwhelming.

We are the alternate personalities of a cosmos suffering from Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). That’s the theory put forward by Bernardo Kastrup in a recent JCS paper and supported by others in Scientific American. I think there’s no denying the exciting elegance of the basic proposition, but in my view the problems are overwhelming.

DID is now the correct term for what used to be called Multiple Personality Disorder, a condition in which different persons appear to inhabit the same body, with control passing between them and allowing them to exhibit distinct personalities, different knowledge, and varied behaviour. Occasionally it has been claimed that different ‘alters’ can even change certain physical characteristics of the host body, within limits. Sceptical analysis notes that the incidence of DID has been strongly correlated with its portrayal in the media. A popular film about multiple personalities always seems to bring a boom in new diagnoses, and in fact an early ‘outbreak’ corresponded with the popularity of ‘Jekyll and Hyde’. Sceptics have suggested that DID may often, or always, be iatrogenic in part, with the patient confabulating the number and type of alter the therapist seems to expect.

Against that, the SA piece cites findings that when blind alters were in control, normal visual activity in the brain ceased. This is undoubtedly striking, though a caveat should be entered over our limited ability to spot what patterns of brain activity go along with confabulation, hypnosis, self-deception, etc. I think the research cited establishes pretty clearly that DID is ‘real’ (though not that patients correctly understand its nature), but then I believe only the hardest of sceptics ever thought DID patients were merely weird liars.

Does DID have the metaphysical significance Kastrup would give it, though? One fundamental problem, to get it up front, is this; if we, as physical human beings, are generated by DID in the cosmic consciousness, and that DID is literally the same thing as the DID observed in patients, how come it doesn’t generate a new body for each of the patient’s alters? There doesn’t seem to be a clear answer on this. I would say that the most reasonable response would be to deny that cosmic and personal DID are exactly the same phenomena and regard them as merely analogous, albeit perhaps strongly so.

Kastrup’s account does tackle a lot of problems. He approaches his thesis by considering related approaches such as panpsychism or cosmopsychism, and the objections to them, notably the combination or decombination problems, which concern how we get from millions of tiny awarenesses, or from one overarching one, to the array of human and animal ones we actually find in the world. His account seems clear and sensible to me, providing convincing brief analyses of the issues.

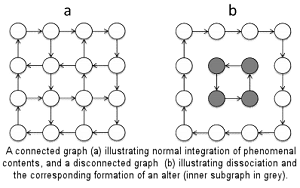

In Kastrup’s system we begin with a universal consciousness which consists of a sort of web of connected thoughts and feelings. Later there will be perceptions, but at the outset there’s nothing to perceive; I’m not sure what the thoughts could be about, either – pure maths, perhaps – but they arise from the inherent tendency of the cosmic consciousness to self-excite (just as a normal human mind, left without external stimulus, does not fall silent, but generates thoughts spontaneously). The connections between the thoughts may be associations, logical connections, inspirational, and so on. I’m not clear whether Kastrup envisages all these thoughts and feelings being active at the same time, or whether new ones can be generated and added in. There is a vast amount of metaphysical work to be done on this kind of aspect of the theory – enough for several generations of philosophers – and it may not be fair to expect Kastrup to have done it all, let alone get it all into this single paper.

I think the natural and parsimonious way to go from there would be solipsism. The cosmic consciousness is all there is, and these ideas about other people and external reality are just part of its random musings. The only argument against this simple position is that our experience insistently and pretty consistently tells us about a world of planets, animals, and evolution which not only forces itself on our attention, but on examination provides some rather good partial explanations of our nature and cognitive abilities. But to accept that argument is to surrender to the conventional view, which Kastrup – he identifies as an idealist – is committed to rejecting.

So instead he takes a different view. Somehow (?), islands of the overall web of cosmic consciousness may get detached. They then become dissociated consciousnesses, and can both perceive and be perceive. Since their associative links with the rest of the cosmos have been broken, I don’t quite know why they don’t lapse into solipsistic beings themselves, unable to follow the pattern of their thoughts beyond its own compass.

In fact, and this may be the strangest thing in the theory, our actual bodies, complete with metabolism and all the rest, are the appearance of these metaphysical islands: ‘living organisms are the revealed appearance of alters of universal consciousness’. Quite why the alters of universal consciousness should look like evolved animals, I don’t know. How does sex between these alters give rise to a new dissociative island in the form of a new human being; what on earth happens when someone starves to death? It seems that Kastrup really wants to have much of the conventional world back; a place where autonomous individuals with private thoughts are nevertheless able to share ideas about a world which is not just the product of their imaginations. But it’s forbiddingly difficult to get there from his starting position. For once, weirder ideas might be easier to justify.

These are, of course, radical new ideas; but curiously they seem to me to bear a strong resemblance to the old ones of the Gnostics. They (if my recollection is right) thought that the world started with the perfect mind of God, which then through some inscrutable accident shed fragmentary souls (us) which became bound in the material world, with their own true nature hidden from them. I don’t make the comparison to discredit Kastrup’s ideas; on the contrary if it were me I should be rather encouraged to have these ancient intellectual forebears.