A new model for robot memory raises some interesting issues. It’s based on three networks, for identification , localization, and working memory. I have a lot of quibbles, but the overall direction looks promising.

A new model for robot memory raises some interesting issues. It’s based on three networks, for identification , localization, and working memory. I have a lot of quibbles, but the overall direction looks promising.

The authors (Christian Balkenius, Trond A. Tjøstheim, Birger Johansson and Peter Gärdenfors)begin by boldly proposing four kinds of content for consciousness; emotions, sensations, perceptions (ie, interpreted sensations), and imaginations. They think that may be the order in which each kind of content appeared during evolution. Of course this could be challenged in various ways. The borderline between sensations and perceptions is fuzzy (I can imagine some arguing that there are no uninterpreted sensations in consciousness, and the degree of interpretation certainly varies greatly), and imagination here covers every kind of content which is about objects not present to the senses, especially the kind of foresight which enables planning. That’s a lot of things to pack into one category. However, the structure is essentially very reasonable.

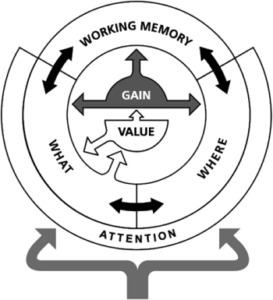

Imaginations and perceptions together make up an ‘inner world’. The authors say this is ess3ntial for consciousness, though they seem to have also said that pure emotion is an early content of consciousness. They propose two tests often used on infants as indicators of such an inner world; tests of the sense of object permanence and ‘A-not-B’. Both essentially test whether infants (or other cognitive entities) have an ongoing mental model of things which goes beyond what they can directly see. This requires a kind of memory to keep track of the objects that are no longer directly visible, and of their location. The aim of the article is to propose a system for robots that establishes this kind of memory-based inner world.

Imitating the human approach is an interesting and sensible strategy. One pitfall for those trying to build robot consciousness is the temptation to use the power of computers in non-human ways. We need our robot to do arithmetic: no problem! Computers can already do arithmetic much faster and more accurately than mere humans, so we just slap in a calculator module. But that isn’t at all the way the human brain tackles explicit arithmetic, and by not following the human model you risk big problems later.

Much the same is true of memory. Computers can record data in huge quantities with great accuracy and very rapid recall; they are not prone to confabulation, false memories, or vagueness. Why not take advantage of that? But human memory is much less clear-cut; in fact ‘memory’ may be almost as much of a ‘mongrel’ term as consciousness, covering all sorts of abilities to repeat behaviour or summon different contents. I used to work in an office whose doors required a four-digit code. After a week or so we all tapped out each code without thinking, and if we had to tell someone what the digits were we would be obliged to mime the action in mid-air and work out which numbers on the keypad our fingers would have been hitting. In effect, we were using ‘muscle memory’ to recall a four-digit number.

The authors of the article want to produce the same kind of ‘inner world’ used in human thought to support foresight and novel combinations. (They seem to subscribe to an old theory that says new ideas can only be recombinations of things that got into the mind through the senses. We can imagine a gryphon that combines lion and eagle, but not a new beast whose parts resemble nothing we have ever seen. This is another point I would quibble over, but let it pass.)

In fact, the three networks proposed by the authors correspond plausibly with three brain regions; the ventral, dorsal, and prefrontal areas of the cortex. They go on to sketch how the three networks play their role and report tests that show appropriate responses in respect of object permanence and other features of conscious cognition. Interestingly, they suggest that daydreaming arises naturally within their model and can be seen as a function that just arises unavoidably out of the way the architecture works, rather than being something selected for by evolution.

I’m sometimes sceptical about the role of explicit modelling in conscious processes, as I think it is easily overstated. But I’m comfortable with what’s being suggested here. There is more to be said about how processes like these, which in the first instance deal with concrete objects in the environment, can develop to handle more abstract entities; but you can’t deal with everything in detail in a brief article, and I’m happy that there are very believable development paths that lead naturally to high levels of abstraction.

At the end of the day, we have to ask: is this really consciousness? Yes and no, I’m afraid. Early on in the piece we find:

On the first level, consciousness contains sensations. Our subjective world of experiences is full of them: tastes, smells, colors, itches, pains, sensations of cold, sounds, and so on. This is what philosophers of mind call qualia.

Well, maybe not quite. Sensations, as usually understood, are objective parts of the physical world (though they may be ones with a unique subjective aspect), processes or events which are open to third-person investigation. Qualia are not. It is possible to simply identify qualia with sensations, but that is a reductive, sceptical view. Zombie twin, as I understand him, has sensations, but he does not have qualia.

So what we have here is not a discussion of ‘Hard Problem’ consciousness, and it doesn’t help us in that regard. That’s not a problem; if the sceptics are right, there’s no Hard stuff to account for anyway; and even if the qualophiles are right, an account of the objective physical side of cognition is still a major achievement. As we’ve noted before, the ‘Easy Problem’ ain’t easy…

Should people be punished for crimes they don’t remember committing? Helen Beebee

Should people be punished for crimes they don’t remember committing? Helen Beebee  It’s not just that we don’t know how anaesthetics work – we don’t even know for sure that they work. Joshua Rothman’s

It’s not just that we don’t know how anaesthetics work – we don’t even know for sure that they work. Joshua Rothman’s  The new Blade Runner film has generated fresh interest in the original film; over on IAI Helen Beebee

The new Blade Runner film has generated fresh interest in the original film; over on IAI Helen Beebee

Carl Zimmer described some interesting research in a recent

Carl Zimmer described some interesting research in a recent