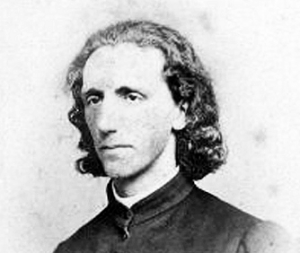

An interesting review by Guillaume Fréchette, of Mark Textor’s new book Brentano’s Mind. Naturally this deals among other things with the claim for which Brentano is most famous; that intentionality is the distinctive feature of the mental (and so of thoughts, consciousness, awareness, and so on). Textor apparently makes five major claims, but I only want to glance at the first one, that in fact ‘Intentionality is an implausible mark of the mental’.

An interesting review by Guillaume Fréchette, of Mark Textor’s new book Brentano’s Mind. Naturally this deals among other things with the claim for which Brentano is most famous; that intentionality is the distinctive feature of the mental (and so of thoughts, consciousness, awareness, and so on). Textor apparently makes five major claims, but I only want to glance at the first one, that in fact ‘Intentionality is an implausible mark of the mental’.

What was Brentano on about, anyway? Intentionality is the property of pointing at, or meaning, or being about, something. It was discussed in medieval philosophy and then made current again by Brentano when he, like others, was trying to establish an empirical science of psychology for the first time. In his view:

“intentional in-existence, the reference to something as an object, is a distinguishing characteristic of all mental phenomena. No physical phenomenon exhibits anything similar.”

Textor apparently thinks that there’s a danger of infinite regress here. He reads Brentano’s mention of in-existence as meaning we need to think of an immanent object ‘existing in’ our mind in order to think of an object ‘out there’; but in that case, doesn’t thinking of the immanent object require a further immanent object, and so on. There seems to be more than one way of escaping this regress, however. Perhaps we don’t need to think of the immanent object, it just has to be there. Maybe awareness of an external object and introspecting an internal one are quite different processes, the latter not requiring an immanent object. Perhaps the immanent object is really a memory, or perhaps the whole business of immanent objects reads more into Brentano than we should.

Textor believes Brentano is pushed towards primitivism – hey, this just is the mark of the mental, full stop – and thinks it’s possible to do better. I think this is nearly right, except it assumes Brentano must be offering a theory, even if it’s only the bankrupt one of primitivism. I think Brentano observes that intentionality is the mark of the mental, and shrugs. The shrug is not a primitivist thesis, it just expresses incomprehension. To say that one does not know x is not to say that x is unknowable. I could of course be wrong, both about Brentano, and particularly about Textor.

What I think you have to do is go back and ask why Brentano thought intentionality was the mark of the mental in the first place. I think it’s a sort-of empirical observation. All thoughts are about, or of, something. If we try to imagine a thought that isn’t about anything, we run into difficulty. Is there a difference between not thinking of anything and not thinking at all (thinking of nothing may be a different matter)? Similarly, can there be awareness which isn’t awareness of anything? One can feel vast possible disputes about this opening up even as we speak, but I should say it is at least pretty plausible that all mental states feature intentionality.

Physical objects, such as stones, are not about anything; though they can be, like books, if we have used the original intentionality of our minds to bestow meaning on them; if in fact we intend them to mean something. Once again, this is disputable, but not, to me, implausible.

Intentionality remains a crucially important aspect of the mind, not least because we have got almost nowhere with understanding it. Philosophically there are of course plenty of contenders; ideas about how to build intentionality out of information, out of evolution, or indeed to show how original intentionality is a bogus idea in the first place. To me, though, it’s telling that we’ve got nowhere with replicating it. Where AI would seem to require some ability to handle meaning – in translation, for example – it has to be avoided and a different route taken. While it remains mysterious, there will always be a rather large hole in our theories of consciousness.

…a alchemical view: Intention is towards the transformation of one’s own coarser materials to finer materials, that our evolution includes the transformation of two states of being human to a third state of being human…

If I’m in a good mood, does that have to be *about* something? I think not.

Intentionality is important, but let’s put it in its place. I think it’s largely orthogonal to qualia issues, for example.

I think there’s a lot to be said for the view that intentionality is prediction (or recognition). We build models / representations / concepts based on sensory input, and then constantly check those models against incoming signals. The models are prediction frameworks, predicting what sensory input we will receive if we approach the thing being modeled, walk around it, whether it will attack us, whether we can eat it, mate with it, etc. This view explains the evolutionary adaptiveness of intentionality, why we have it, and describes what it is in non-mental terms.

If true, then I’d say we are making progress in reproducing it. Self driving cars and other autonomous robots do build models along these lines, but they remain pale imitations of what any animal with distance senses can do.

Pingback: The Mark of the Mental – Health and Fitness Recipes

An orthogonal view, linear and non linear activity should be present(ed) together, intentionally creating a state of *knowing and not knowing* and place for qualia to more clearly appear and be worked with…thanks #2

“What I think you have to do is go back and ask why Brentano thought intentionality was the mark of the mental in the first place…I should say it is at least pretty plausible that all mental states feature intentionality.”

Agreed, or at least I’d say that intentionality is the basic raison d’etre of mental states even if some lack it. Minds are generally in the business of controlling behavior in service to the host system’s safe passage through the world, which of course in complex, future-predicting systems like us requires modeling (mentally simulating) the world, the system itself, and their relation. So it’s an essential requirement that the model/simulation have a good enough correlation with what it represents, which is where reference and intentionality come in. Seems to me there has to be some sort of causal connection, however attenuated and however it’s mediated, between the system’s deployment of a term (in thought or speech), and that which the term refers to. I would think that the study of simpler artificial systems that possess behavior controlling world-models could illuminate how successful reference (and thus the possibility of misrepresentation) arises out of iterated interactions with the environment. There can’t be any insuperable mystery to intentionality since it’s a natural phenomenon.

To understand the meaning of a term is simply to be able to act appropriately in situations when the term is

“To understand the meaning of a term is simply to be able to act appropriately in situations when the term is…deployed.”

One way of cashing out “original intentionality” in terms of behavior, perhaps.

Yes SelfAwarePaterns,

and the evolutionary adaptiveness of intentionality also indicates an entry point for its possible naturalization.

But phenomenology does not look as having accepted an anthropologic/evolutionary perspective (perhaps because of the associated naturalization risk).

As a consequence the concept of bio-intentionality is not really part of the today philosophical world. This is too bad because it would allow a simpler starting point not having to consider self-consciousness. More workable for a bottom up approach.

Still a lot to do…

Two first reactions: 1) a brain in a vat or a disembodied mind can have thoughts even if it is the only thing in the universe or vicinity 2) My thoughts ‘about’ a thing may be about appearances and not about real or essential properties, so they are about things that don’t exist, say the example of color.

Peter

“Physical objects, such as stones, are not about anything”

Interesting though because a ‘stone’ exists only to the eye of an intentional viewer. In a sense a ‘stone’ is in fact an entirely intentional idea. Intrinsically a stone is no different to any other point in space – it has particles and force fields like everywhere else – yet humans and other animals can isolate the space around a stone by virtue of their visual systems, and sense of touch identifies it as a solid.

There are intrinsic characteristics of stones that exist too – but these characteristics are based upon belief, the belief that matter consists of atoms and molecules and that light bounces off them etc. But the starting point is the sensory object – the solid to the touch, non-transparent object that the conscious agent can form a theory about.

So in fact – strictly speaking – stones subsist solely as the object of intentional thought, and as blocks of knowledge are syntheses of of cognition.

JBD