Adam Pautz has a new argument to show that consciousness is irreducible (that is, it can’t be analysed down into other terms like physics or functions). It’s a relatively technical paper – a book length treatment is forthcoming, it seems – but at its core is a novel variant on the good old story of Mary the Colour Scientist. Pautz provides several examples in support of his thesis, and I won’t address them all, but a look at this new Mary seems interesting.

Adam Pautz has a new argument to show that consciousness is irreducible (that is, it can’t be analysed down into other terms like physics or functions). It’s a relatively technical paper – a book length treatment is forthcoming, it seems – but at its core is a novel variant on the good old story of Mary the Colour Scientist. Pautz provides several examples in support of his thesis, and I won’t address them all, but a look at this new Mary seems interesting.

Pautz begins by setting out a generalised version of how plausible reductive accounts must go. His route goes over some worrying territory – he is quite Russellian, and he seems to take for granted the old and questionable distinction between primary and secondary qualities. However, if the journey goes through some uncomfortable places, the destination seems to be a reasonable place to be. This is a moderately externalist kind of reduction which takes consciousness of things to involve a tracking relation to qualities of real things out there. We need not worry about what kinds of qualities they are for current purposes, and primary and secondary qualities must be treated in a similar way. Pautz thinks that if he can show that reductions like this are problematic, that amounts to a pretty good case for irreducibility.

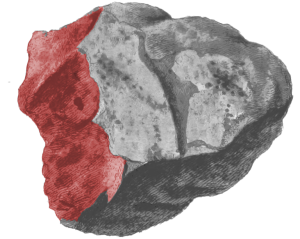

So in Pautz’s version, Mary lives on a planet where the outer surfaces of everything are black, grey, or white. However, on the inside they are brilliantly coloured, with red, reddish orange, and green respectively. All the things that are black outside are red inside, and so on, and this is guaranteed by a miracle ‘chemical’ process such that changes to the exterior colour are instantly reflected in appropriate changes inside. Mary only sees the outsides of things, so she has never seen any colours but black, white and grey.

Now Mary’s experience of black is a tracking relation to black reflectances, but in this world it also tracks red interiors. So does she experience both colours? If not, then which? A sensible reductionist will surely say that she only experiences the external colour, and they will probably be inclined to refine their definitions a little so that the required tracking relation requires an immediate causal connection, not one mediated through the oddly fixed connection of interior and exterior colours. But that by no means solves the problem, according to Pautz. Mary’s relation to red is only very slightly different to her relation to black. Similar relations ought to show some similarity, but in this case Mary’s relation to black is a colour experience, whereas her relation to red, intrinsically similar, is not a colour experience – or an experience of any kind! If we imagine Martha in another world experiencing a stone with a red exterior, then Martha’s relation to red and Mary’s are virtually identical, but have no similarity whatever. Suppose you had a headache this morning, suggests Pautz, could you then say that you were in a nearly identical state this afternoon, but that it was not the state of experiencing a headache; in fact it was no experience at all (not even, presumably, the experience of not having a headache).

Pautz thinks that examples of this kind show that reductive accounts of consciousness cannot really work, and we must therefore settle for non-reductive ones. But he is left offering no real explanation of the relation of being conscious of something; we really have to take that as primitive, something just given as fundamental. Here I can’t help but sympathise with the reductionists; at least they’re trying! Yes, no doubt there are places where explanation has to stop, but here?

What about Mary? The thing that troubles me most is that remarkable chemical connection that guarantees the internal redness of things that are externally black. Now if this were a fundamental law of nature, or even some logical principle, I think we might be willing to say that Mary does experience red – she just doesn’t know yet (perhaps can never know?) that that’s what black looks like on the inside. If the connection is a matter of chance, or even guaranteed by this strange local chemistry, I’m not sure the similarity of the tracking relations is as great as Pautz wants it to be. What if someone holds up for me a series of cards with English words on one side? On the other, they invariably write the Spanish equivalent. My tracking relation to the two words is very similar, isn’t it, in much the same way as above? So is it plausible to say I know what the English word is, but that my relation to the Spanish word is not that of knowing it – that in fact that relation involves no knowledge of any kind? I have to say I think that is perfectly plausible.

I can’t claim these partial objections refute all of Pautz’s examples, but I’m keeping the possibility of reductive explanations open for now.

Peter,

I loved Pautz’s essay, it was another example of the alluring attraction that our form of consciousness has upon our own experiences of it. I applaud the effort and the work Paul put into his research, but I do agree with you Peter, this is no place to stop, because consciousness is irreducible to something that is a fundamental qualitative property of all discrete forms of consciousness. The problem is, that the very term consciousness is a rogue idiom, one that has never been contained within a single definition of which that everyone is in agreement.

Chalmers is recognized for canonizing his zombie metaphor. I too have a metaphor that hopefully will rise to the same level of prominence, accredited to me of course, it is the silly putty metaphor.

It goes like this:

I have this visual in my head of a group of five year olds playing with silly putty every time I read books, articles or discussions about consciousness. Like consciousness, silly putty is some really cool stuff, it does all of these neat things; it’s flexible, one can squish it into all kinds of shapes, it bounces like a ball, and one can even press it onto a colored image of the Sunday funny papers and lift that colored image off the page. But like consciousness, silly putty is something rudimentary and fundamental; silly putty is a single chain of Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen and Silicone mediated by Boron and crossed linked to give it its elasticity putty like behavior.

There is an irony in this allegory; if one of the five year olds pointed out the fundamental chemical properties of the silly putty to his other playmates, they probably couldn’t care less for two simple reasons. First, the other children wouldn’t understand simple chemistry and second, the magic and allure of this mysterious stuff called silly putty would loose it magical, mystical appeal. In other words, it wouldn’t be fun any more. I have this nagging hunch that the phenomenon of consciousness might be the same way, something rudimentary and fundamental, so rudimentary that it may even shame our own self inflated intellect. Albeit, at the end of the day, that explanation of consciousness will be a metaphysical one.

The way we esoteric’s put it…observation is independent in cosmology–for fundamental interactions and one’s own interactions to be a posteriori phenomena from a priori noumenon, or pluralism with no end insight…

…that we ought to be consciousness could be our most primordial instinctive value…

[Note: this from a complete reductionist]

I’m afraid I have all kinds of problems with Mr. Pautz’s paper. My BS-alert meter first pinged when he mentioned “the timeless necessary truth that blue is more like purple than green”. Um, since when? (Oh, right, timeless).

And then later, “of course, Mary causally detects the inner colors as much as the outer colors.” What does “causally detect” mean? Certainly it cannot mean consciously experience, right? Because there is no useful sense in which to say Mary consciously experiences the redness inside the rock in the same way she would experience the redness outside the rock. At best, Mary could experience a concept of red, but there is no reason to say that her experience of black is also an experience of red.

And so I’m not sure what Peter means when he says “Martha’s relation to red and Mary’s relation to red are virtually identical”. Do you mean potentially? Because Martha has experienced red and Mary has not.

What am I missing?

*

Yes, I can’t really get the argument? Is there some notion that the black surface is somehow connected to the inner red rock – thus some kind of experiential connection?

What if the rock is black all the way through? Is there supposed to be an experiential difference between a rock that is black all the way through and a rock which is black on the surface but red inside?

I don’t know if I’m mssing something but clearly objects don’t have colours and can’t be ppoperties of objects, at least for the purpose of a discussion on consciousness and epistemology.

An external relationship between compounds does not determine the reaction that the brain has to the light being emitted from either surface, so the whole argument seems totally specious to me. Clearly the girl sees what she sees, and doesn’t see the interiors and therefore the ‘colour’ of the interior is never realised, hence it’s discussion as on objective fact is incorrect.

J

John, The discussion is interesting because that is exactly how we see. The world is black and white or colorless and our brains track it by the neurons inside of us which track or change state in accordance with the reflected and absorbed light spectrum wrt those objects. Shows how much of our thought process is a hack of our visual processing mechanisms. The key to the argument is that our biology “mysteriously” changes state wrt to the external environment and those state changes we perceive are the ones we easily talk about or end up as language. Very similar to those mysterious forces Newton discovered that explained the mathematics of tracking planets. Before Newton they lived in a world of tracking, computations or the scientific cartoon of data and “planet correlates”.

“Mary’s experience of black is a tracking relation to black reflectances, but in this world it also tracks red interiors. So does she experience both colours?”

Trying to figure this out – what does ‘tracks’ mean here? Basically some chemical process always makes the outside of the rock black. Mary’s eyes are completely unaware of this process. These are two different types of trackings, aren’t they? We’re getting an apples and oranges comparison.

Callan, I interpret “track” to mean there is a causal history that leads from a system in question to the “experience”. For ease of explanation, let’s change black to blue. Thus, when white light falls on the sphere, blue light is reflected. Blue light enters the eyeball, triggering a neural response which triggers other neural responses, etc., eventually triggering what counts as a blue experience.

Pautz notes that the causal history chain can be extended one link to something red, and so he is positing (I think) that the red thing is part of the experience. The problem is that there is a pre-existing mechanism that associates blue light hitting the retina to blue objects out in the world so when that happens we call it a blue experience. There is no such mechanism to associate blue light with red things, at least not until we have knowledge that there is such a connection. It may well be that, having such knowledge, seeing blue things may initiate a type of “redness” experience, very possibly a memory of seeing red. But obviously Mary has neither such memory nor knowledge, and so presumably no such experience from seeing blue.

*

Lee Roetcisoender, I would say I agree. My definition is the pansychist perspective because what we do is exactly what every fundamental particle is doing. Every particle either attracts, repels or is neutral wrt other particles or it is interacting with its environment. We do exactly the same with our brains except we construct larger representations and still interact with them like fundamental particles. Only difference is our brains have performed this magical scaling function so though we are blind to the particle level in our neurons, this scaled world function still can be reduced to a computational/correlate etc. level. At the biological level it is not the particles but actually the forces that make them attract/repel/act neutral so this mysterious thing called mind emerges from them.

VicP,

Just to be clear so nobody misunderstands, I am a noumenalist, so my model of consciousness is predicated upon panpsychism, specifically micro-panpsychism. I do believe your brief analysis of consciousness is spot on, that’s exactly why I crafted the silly putty metaphor. Primordial, fundamental properties of and by themselves are boring and boorish. Nevertheless, both silly putty and our first person objective experience of consciousness is some pretty cool stuff. And if you noticed, I used the term objective experience instead of subjective experience. I hope I didn’t offend anyone.

Out of curiosity VicP, do you have a model of consciousness yourself?

And still we are here, not so much from irreducible fundamental objects in space or from their fundamental interactions, but from the irresistible unknown…

Arnold,

The “irresistible unknown” is the very predicate for and targeted objective of Western syllogistic logic. Richard Rorty felt it best that philosophers just simply abandon the search and move on, not that I necessarily disagree with the man. In a pragmatic context though, I don’t think that is going to happen any time soon…….

Esoteric idealists and noumenalists don’t play well together

James

“The problem is that there is a pre-existing mechanism that associates blue light hitting the retina to blue objects out in the world so when that happens we call it a blue experience.”

Yes. This is a resurfacing of the confusion of experience, the cause of the experience, and mere antecedent events. Blue light is not blue, but it triggers a blue experience in the head. Blue light is an antecedent, but not necessary, event for a blue experience. ( I can think of blue/dream of it etc). To talk of a cause of a mental experience we really do have to restrict our scope to what ges on in the brain : the rest are mere antecedent events.

So Mary has an objective relationship to the interior colour when viewed from a third party perspective, but she is in no way experiencing the interior light. But nor is she experiencing the the exterior surface either, in exactly the same way. The light from the exterior surface is triggering her brain to generate mental images, and the brains’ activity constitute the entirety of that experience.

JBD

Thanks, James. Though I still don’t really understand – it almost seems like synethesia. But instead of mixing senses together Pautz seems to be mixing memories together as if they are one and the same – but as you say, Mary has no knowledge of red.

It also seems to treat objects as ‘having’ colour. I went to a talk last night that reminded me of something – in it there was an animation of a malaria virus invading a red blood cell. The malaria virus was coloured green. However someone asked latter if that is the real colour, to which the person who’d made the animation replied that really such objects are smaller than the wavelengths of light. So they can ‘have’ no colour at all, really. The green colour was just assigned for ease of our mammalian way of thinking, to almost directly quote the person.

In a way our attributing objects as ‘having’ colour is misplaced.

Blue light is not blue, but it triggers a blue experience in the head

The fundamental problem in such discussions is that “colors” are just names we learn as children to associate with certain phenomenal experiences (PE). Nothing is “blue” in the sense we usually use such a color name, viz, to describe a surface. As John notes, light can’t be “blue” in the surface sense., although It can be considered to be blue in the straightforward sense that its spectral power distribution (SPD) is concentrated in a certain portion of the visible (to us) spectrum.

Neither can a PE be “blue” in the surface sense. Visual sensory stimulation by blue (in the SPD sense) light causes a person to have a PE that the person usually has learned to associate with with the word “blue”. The neural activity underlying the PE clearly isn’t “blue” in the surface sense, but neither is the PE itself. One can of course choose to define “blue” as being that PE, but colors in that sense wouldn’t necessarily have the properties usually associated with color names. Eg, it isn’t obvious in what sense a “blue PE is closer to a purple PE than to a green PE”; your blue PE and my blue PE are unlikely to be the same even though both of us probably will describe a surface reflecting blue (SPD sense) light as “blue”; etc.

It would be awfully nice if Mary were left in peace to enjoy her new found color experiences instead of constantly being outfitted in new, almost always, ill-fitting garb.

Roetcisoender…

If esoteric is here-ness…

…then staying with here-ness is esoteric…