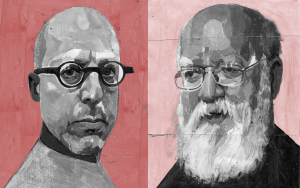

Dan Dennett and Gregg Caruso had a thoughtful debate about free will on Aeon recently. Dennett makes the compatibilist case in admirably pithy style. You need, he says, to distinguish between causality and control. I can control my behaviour even though it is ultimately part of a universal web of causality. My past may in the final sense determine who I am and what I do, but it does not control what I do; for that to be true my past would need things like feedback loops to monitor progress against its previously chosen goals, which is nonsensical. This concept of being in control, or not being in control, is quite sufficient to ground our normal ideas of responsibility for our actions, and freedom in choosing them.

Dan Dennett and Gregg Caruso had a thoughtful debate about free will on Aeon recently. Dennett makes the compatibilist case in admirably pithy style. You need, he says, to distinguish between causality and control. I can control my behaviour even though it is ultimately part of a universal web of causality. My past may in the final sense determine who I am and what I do, but it does not control what I do; for that to be true my past would need things like feedback loops to monitor progress against its previously chosen goals, which is nonsensical. This concept of being in control, or not being in control, is quite sufficient to ground our normal ideas of responsibility for our actions, and freedom in choosing them.

Caruso, who began by saying he thought their views might turn out closer than they seemed, accepts pretty well all of this, agreeing that it is possible to come up with conceptions of responsibility that can be used to underpin talk of free will in acceptable terms. But he doesn’t want to do that; instead he wants to jettison the traditional outlook.

At this point Caruso’s motivation may seem puzzling. Here we have a way of looking at freedom and responsibility which provides a philosophically robust basis for our normal conception of those two moral basics – ideas we could not easily do without in our everyday lives. Now sometimes philosophy may lead us to correct or reject everyday ideas, but typically only when they appear to be without rational justification. Here we seem to have a logically coherent justification for some everyday moral concepts. Isn’t that a case of ‘job done’?

In fact, as he quickly makes clear, Caruso’s objections mainly arise from his views on punishment. He does not believe that compatibilist arguments can underpin ‘basic desert’ in the way that would be needed to justify retributive punishment. Retribution, as a justification for punishment, is essentially backward looking; it says, approximately, that because you did bad things, bad things must happen to you. Caruso completely rejects this outlook, and all justifications that focus on the past (after all, we can’t change the past, so how can it justify corrective action?). If I’ve understood correctly, he favours a radically new regime which would seek to manage future harms from crime in broadly the way we seek to manage the harms that arise from ill-health.

I think we can well understand the distaste for punishments which are really based on anger or revenge, which I suspect lies behind Caruso’s aversion to purely retributive penalties. However, do we need to reject the whole concept of responsibility to escape from retribution? It seems we might manage to construct arguments against retribution on a less radical basis – as indeed, Dennett seeks to do. No doubt it’s right that our justification for punishments should be forward looking in their aims, but that need not exclude the evidence of past behaviour. In fact, I don’t know quite how we should manage if we take no account of the past. I presume that under a purely forward-looking system we assess the future probability of my committing a crime; but if I emerge from the assessment with a clean bill of health, it seems to follow that I can then go and do whatever I like with impunity. As soon as my criminal acts are performed, they fall into the past, and can no longer be taken into account. If people know they will not be punished for past acts, doesn’t the (supposedly forward-looking) deterrent effect evaporate?

That must surely be wrong one way or another, but I don’t really see how a purely future-oriented system can avoid unpalatable features like the imposition of restrictions on people who haven’t actually done anything, or the categorisation of people into supposed groups of high or low risk. When we imagine such systems we imagine them being run justly and humanely by people like ourselves; but alas, people like us are not always and everywhere in charge, and the danger is that we might be handing philosophical credibility to people who would love the chance to manage human beings in the same way as they might manage animals.

Nothing, I’m sure, could be further from Gregg Caruso’s mind; he only wants to purge some of the less rational elements from our system of punishment. I find myself siding pretty much entirely with Dennett, but it’s a stimulating and enlightening dialogue.

Peter

“I can control my behaviour even though it is ultimately part of a universal web of causality.”

Need anyone say more ? It doesn’t matter how much utter nonsense he spouts, Dennett jut seems to get away with it. That’s the tyranny of academic reputation. The emperor wears no clothes – such as spouting self-evident oxymorons – and another academic lazily accepts it, because he wants to get on with his agenda, led by politics too, like Dennett.

JBD

It seems a case of why we would punish someone, not so much whether we would. Caruso thinks it wrong to give someone their just deserts when they do something wrong because they are not morally responsible and therefore do not deserve retribution. It is acceptable, though, to punish them to cement in place a social code that prescribes acceptable and unacceptable behaviours as that is forward looking.

Dennett’s position is that we develop free will and therefore moral control over time. One has to question where our free will decisions come from, though. They are built on the values and beliefs we have accumulated and so are largely hidden when we actually make a decision. Just being unaware of why you make a decision doesn’t make it free will.

Dennett says:

“Autonomous people are justly held responsible for what they did because all of us depend on being able to count on them”

but this really is just an attempt to avoid the free will skeptic argument. A behavioural model can as easily be applied here as a moral responsibility one.

Dennett goes off the rails when he says:

“Your past does not control you; for it to control you, it would have to be able to monitor feedback about your behaviour and adjust its interventions – which is nonsense.”

He is saying that your past is not you. It is some other entity that can cause the real you to do something different than what you want. In reality, what you want is dependent on your past.

In the end, moral responsibility is a useful, if imperfect, fiction that is really a means of helping to maintain beneficial social behaviours.

As John Davey notes Dennet’s position is just illogical.

I don’t know if the motivation is politics but there is something disturbing that something as obviously (laughably?) wrong as compatibilism continues to see acceptance in philosophy academia.

Wanting free will vs wanting the will to become free…

That thinking about free will may lead to wanting free will..

…and understanding sacrifice, as paying for the will to become free…

Is suffering-value-itself, searching to acquire the will to become free…

Peter,

I think you concede too much with “No doubt it’s right that our justification for punishments should be forward looking in their aims.” Well, it should be both forward-looking and sideways-looking: with the sideways view being a concern for fairness and even-handedness. And it’s that concern for fairness that motivates the fact that the actual rules of punishment are backward-looking and *not* forward-looking.

I suspect that Caruso and most on his side want to create some further moral standard for “desert”, beyond the fact that the best rules we can come up with call for punishment. I just don’t see what that further standard is supposed to be. People used to think that romantic love was a matter of being shot with an invisible magic arrow by a cherubic god. Imagine someone who said “there’s no such thing as romantic love, because there’s no such god as Eros.” That critic would stand to romantic love as Caruso stands to desert, in my view – and probably in Dennett’s, since it’s his analogy, which I stole fair and square.

Stephen,

When Dennett says for something to control you “it would have to be able to monitor feedback about your behaviour and adjust its interventions,” he’s just reiterating the definition of control. It’s a standard definition, straight out of an engineering Control Theory text.

john davey,

Oxymorons? Maybe the intuitive idea of causality (projected onto the world from our own experience of pushing stuff around), extended to the universe, conflicts with control of one’s own behavior. The scientific picture of causality doesn’t.

but if I emerge from the assessment with a clean bill of health, it seems to follow that I can then go and do whatever I like with impunity. As soon as my criminal acts are performed, they fall into the past, and can no longer be taken into account. If people know they will not be punished for past acts, doesn’t the (supposedly forward-looking) deterrent effect evaporate?

Well that’d be the creepy thing – they’d be evaluating your behavior sans any deterrent. And if the evaluation is that you wont do anything bad, then you wont. Rather than being hemmed in with punishments, you’d be hemmed in by your own behavioral constraints.

That is with perfect prediction. This is all getting a bit ‘Minority Report’ – and that had an interesting take on supposed perfect prediction.

Paul

Maybe the intuitive idea of causality (projected onto the world from our own experience of pushing stuff around), extended to the universe, conflicts with control of one’s own behavior. The scientific picture of causality doesn’t.

I should stress that I don’t actually advocate determinism or free will. What I do know is you can’t advocate both in the same sentence. That is tosh, pure and simple. A liberal advocate getting to have his cake and eat it.

If the state of the Universe at time T is linked to the state at time T+d, then if you are a materialist that link is solely based upon P(U(T)), the distribution of possible quantum states arising from the state of the Universe at time T. There are no intervening mechanisms : no control. “Control” implies there are such things as human beings, which of course don’t exist in quantum physics (or indeed any physics) so any argument which links control and physics in the same sentence is usually an ontological mish mash which is ultimately incoherent.

I don’t think your link helps us in this regard. It’s not a scientific view of compatibilism (which can’t exist in any case as no such proof is currently possible) it’s a philosophers dennett-like incoherent defence of the indefensible. I would beware of anybody wielding the quantum stick and using it’s inherent ambiguities to plug gaps in human quandaries.

All compatibilism suffer from the same problems : they swap ontologies and frames of reference at the drop of a hat to make the argument stick. But if you buy the notion that the laws of physics determine everything and that brains and minds are governed by those laws then that alone is sufficient to say that there is no such thing as free will and to say otherwise is total and inherent guff, the kind of tosh a lawyer would write to say his client didn’t do it. Use enough words and we’ll forget the main point in the haze of the intentionally vague conceptual apparatus and and nudge and wink smudging of the otherwise indelible pattern : if the laws of physics are sufficient to account for minds (something i don’t advocate incidentally) then you cannot – simply cannot believe in free will.

Either of the main alternatives I actually have no disagreement with. How could I ? They both make sense. But the merge of the two is the biggest load of nonsense in philosophy today

JBD

@ John Davey:

So by political do you mean any defense of humanist values and the usually idea of moral accountability must be incompatible with the physical closure Dennett proposes?

It does seem Dennett is hoping to squeeze even the possibility of exceptions to physical closure out of the picture, and this is why he has to argue everything about reality is reducible to non-conscious elements.

Is any of that political though? Is it b/c you think Dennett is playing this con-game of compatibilism as a means of advancing a metaphysics that shuts out any potential for a Creator?

Well John Davey, I must be a dummy because I don’t see how “there are no human beings” follows from physics being applicable to the entire universe. It looks like a fallacy of composition to me. As for interventions, they apply only from one part of the universe to another, the universe doesn’t intervene on itself – and the universe doesn’t cause its own states, on Pearl’s definition of causality. That doesn’t deprive us of the ability to intervene, since we’re parts of the universe, acting on other parts. The link doesn’t “wield the quantum stick”; it mentions quantum physics only to point out that it’s *not* vital to the argument.

I have to say that I largely agree with Caruso’s view. I think that as a society we must recognize that we largely lack free will but maintain a legal system with individual responsibility at its core.

Sci

So by political do you mean any defense of humanist values and the usually idea of moral accountability must be incompatible with the physical closure Dennett proposes?

Exactly. Dennett’s passion is more politics than anything else if you ask me. It’s what drives him. He tailor makes his philosophical conclusions to match his political goals – and it’s nonsense. Dennett wants accountability because he wants the right wing conservatives held to account. But he doesn’t want God either – and in his very limited scope of epistemology that means denying mental phenomena exist.

Paul

If you look in any physics textbook, you won’t find the definition of a human being. Biological entities and concepts have no scope in physics (this isn’t controversial by the way, don’t take my word for it). Humans can be introduced in an an adhoc way into physical pictures as an assemblage of particles. But the point is, left to it’s own devices, physics doesn’t know what humans are. That’s a big limitation. The laws of physics are particulate and aggregate and no collection of particles is any different to any other. Physics doesn’t distinguish me from arm or my nose or my brain or me from you or the bacteria in my colon or anything.

So to introduce biological concepts such as ‘sex’ or ‘mouse’ or ‘urinate’ or ‘control’ is totally nonsensical and meaningless to a “physical” ( as in “physics based”) framework : it is a literally pointless exercise as it has no effect on anything. At all. In any way. So noone controls anything because – in a particulate world – there are no biological entities to do the controlling in the first place. Particles do what they do and they do them influenced only by physcial forces of the particles near enough to to influence them. And that’s it.

There is incidentally a huge and vast minsunderstanding of ’cause’ in the world of physics. Physics imagery is one of a mathematical continuum. The meaning of the word ’cause’ in physics has no value other than as a teaching aid. As far as physics is concerned, to say that ‘a caused b’ is not relevant to the history of the universe.

One point in time is much the same as another, and one state flows into the other continuously. We can’t say ‘state b causes state c’ as the point time prior to ‘b’, which we’ll call ‘a’ – is just as significant as ‘state b’ in the creation of ‘state c’. We can’t point at any single point in time and say “that state causes that state”. Single aspect cause, as used in common diction, is a totally meaningless notion in a physics history of the universe. It literally only has value as a teaching aid. Theoretical physicists seldom make these points clear – what else is new, scientists are pretty hopeless philosophers and vice versa.

J

John Davey,

There’s a big difference between “the witness doesn’t claim to know about the events in question” and “the witness says the events didn’t happen”. If you can’t see the difference, there’s a Supreme Court clerkship available to you under Brett Kavanaugh. Physics doesn’t mention human beings as such, but that doesn’t mean there are no human beings in physics. Compare a topographical map, and the cities in the territory it maps. Even though the map doesn’t name my city, if I know enough about my city to locate it on the map, I can learn a lot more about my city than what I started with.

Physicists have their own definition of “determinism”. I thoroughly agree with your point that it bears no obvious relation to common diction about causality. But if we want to talk about the implications of “scientific determinism”, we should use the scientists’ definition. (And if other philosophers want to talk about some other “determinism”, theological for example, I find that less interesting.)

Perhaps I’ve missed something but the American political references are confusing.

It simply seems to me that if everything reduces to physics human decisions reduce to physics, which means Dennet’s attempts to siphon out some kind of moral system are obviously wrong.

I suspect this is the sort of chasm between interlocutors that ensures the big questions of Consciousness will never have some grand Answer – we all have prior, for lack of a better word, “aesthetic” commitments to how we think the world should work.

Paul

There was no such thing as the “determinism” quandrary until physics arrived. Physics is a technique – not a philosophy or a gift from god. Its’ a technique based upon primitive properties and mathematical calculus. There are no human beings in it any any point. The language of ’cause’ and ‘effect’ does not actually arise, except in a generic sense – NOT in the agency sense which applies to the determinism argument and which requires – in the scope of the analytical tools being used – a meaningful definition of “human being”.

It’s the huge hole that sits in a lot of analysis on the subject, and Dennett’s treatment of it is even more dishonest than most of his other nonsense (ie let’s talk about consciousness which doesn’t exist etc)

JBD