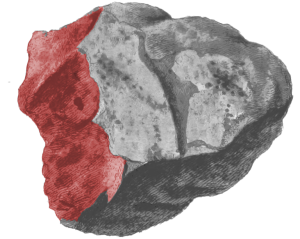

A new type of neuron is a remarkable discovery; finding one in the human cortex makes it particularly interesting, and the further fact that it cannot be found in mouse brains and might well turn out to be uniquely human – that is legitimately amazing. A paper (preprint here) in Nature Neuroscience announces the discovery of ‘rosehip’ neurons , named for their large, “rosehip”-like axonal boutons.

A new type of neuron is a remarkable discovery; finding one in the human cortex makes it particularly interesting, and the further fact that it cannot be found in mouse brains and might well turn out to be uniquely human – that is legitimately amazing. A paper (preprint here) in Nature Neuroscience announces the discovery of ‘rosehip’ neurons , named for their large, “rosehip”-like axonal boutons.

There has already been some speculation that rosehip neurons might have a special role in distinctive aspects of human cognition, especially human consciousness, but at this stage no-one really has much idea. Rosehip neurons are inhibitory, but inhibiting other neurons is often a key function which could easily play a big role in consciousness. Most of the traffic between the two hemispheres of the human brain is inhibitory, for example, possibly a matter of the right hemisphere, with its broader view, regularly ‘waking up’ the left out of excessively focused activity.

We probably shouldn’t, at any rate, expect an immediate explanatory breakthrough. One comparison which may help to set the context is the case of spindle neurons. First identified in 1929, these are a notable feature of the human cortex and at first appeared to occur only in the great apes – they, or closely analogous neurons, have since been spotted in a few other animals with large brains, such as elephants and dolphins. I believe we still really don’t know why they’re there or what their exact role is, though a good guess seems to be that it might be something to do with making larger brains work efficiently.

Another warning against over-optimism might come from remembering the immense excitement about mirror neurons some years ago. Their response to a given activity both when performed by the subject and when observed being performed by others, seemed to some to hold out a possible key to empathy, theory of mind, and even more. Alas, to date that hope hasn’t come to anything much, and in retrospect it looks as if rather too much significance was read into the discovery.

The distinctive presence of rosehip neurons is definitely a blow to the usefulness of rodents as experimental animals for the exploration of the human brain, and it’s another item to add to the list of things that brain simulators probably ought to be taking into account, if only we could work out how. That touches on what might be the most basic explanatory difficulty here, namely that you cannot work out the significance of a new component in a machine whose workings you don’t really understand to begin with.

There might indeed be a deeper suspicion that a new kind of neuron is simply the wrong kind of thing to explain consciousness. We’ve learnt in recent years that the complexity of a single neuron is very much not to be under-rated; they are certainly more than the simple switching devices they have at times been portrayed as, and they may carry out quite complex processing. But even so, there is surely a limit to how much clarification of phenomenology we can expect a single cell to yield, in the absence of the kind of wider functional theory we still don’t really have.

Yet what better pointer to such a wider functional theory could we have than an item unique to humans with a role which we can hope to clarify through empirical investigation? Reverse engineering is a tricky skill, but if we can ask ourselves the right questions maybe that longed-for ‘Aha!’ moment is coming closer after all?