We’ve heard some thin arguments recently about why the robots are not going to take over, centring on the claim that they lack human style motivation, and cannot care what happens or want power. This neglects the point that robots (I use the term for any loosely autonomous cybernetic entity whether humanoid in shape or completely otherwise) might still carry out complex projects that threaten our well-being without human motivation; but I think there is something in the contention about robots lacking human-style ambition. There are of course many other arguments for the view that we shouldn’t worry too much about the robot apocalypse, and I think the conclusion that robots are not about to take over is surely correct in any case.

We’ve heard some thin arguments recently about why the robots are not going to take over, centring on the claim that they lack human style motivation, and cannot care what happens or want power. This neglects the point that robots (I use the term for any loosely autonomous cybernetic entity whether humanoid in shape or completely otherwise) might still carry out complex projects that threaten our well-being without human motivation; but I think there is something in the contention about robots lacking human-style ambition. There are of course many other arguments for the view that we shouldn’t worry too much about the robot apocalypse, and I think the conclusion that robots are not about to take over is surely correct in any case.

What I’d like to do here is set out an argument of my own, somewhat related to the thin ones mentioned above, in more detail. I’ve mentioned this argument before, but only briefly.

First, some assumptions. My argument rests on the view that we are dealing with two different kinds of ‘mental’ process. Specifically, I assume that humans have a cognitive capacity which is distinct from computation (in roughly a traditional Turing sense). Further I assume that this capacity, ‘humation’, as I’ll call it, supplies us with our capacity for intentionality, both in the sense of being able to deal with meanings, and in the sense of being able to originate new future-directed plans. Let’s round things out by assuming it also provides phenomenal experience and anything else uniquely human (though to be honest I think things are probably not so tidy).

I further assume that although humation is not computation, it can in principle be performed by some as-yet-unknown machine. There is no magic in the brain, which operates by the laws of physics, so it must be at least theoretically possible to put together a machine that humates. It can be argued that no artefactual machine, in the sense of a machine whose functioning has been designed or programmed into it, could have a capacity for humation. On that argument a humater might have to be grown rather than built, in a way that made it impossible to specify how it worked in detail. Plausibly, for example, we might have to let it learn humation for itself, with the resulting process remaining inscrutable to us. I don’t mind about that, so long as we can assume we have something we’d call a machine, and it humates.

Now we worry about robots taking over mainly because of the many triumphs and rapid progress of computers (and, to be honest, a little because of a kind of superstition about things that seem spookily capable). On the one hand, Moore’s law has seen the power of computers grow rapidly. On the other, they have steadily marched into new territory, proving capable of doing many things we thought were beyond them. In particular, they keep beating us at games; chess, quizzes, and more recently even the forbiddingly difficult game of Go. They can learn to play computer games brilliantly without even being told the rules.

Games might seem trivial, but it is exactly that area of success that is most worrying, because the skills involved in winning a game look rather like those needed to take over the world. In fact, taking over the world is explicitly the objective of a whole genre of computer games. To make matters worse, recent programs set to learn for themselves have shown an unexpected capacity for cheating, or for exploiting factors in the game environment or even in underlying code that were never meant to be part of the exercise.

These reflections lead naturally to the frightening scenario of the Paperclip Maximiser, devised by Nick Bostrom. Here we suppose that a computer is put in charge of a paperclip factory and given the simple task of making the number of paperclips as big as possible. The computer – which doesn’t actually care about paperclips in any human way, or about anything – tries to devise the best strategies for maximising production. It improves its own capacity in order to be able to devise better strategies. It notices that one crucial point is the availability of resources and energy, and it devises strategies to increase and protect its share, with no limit. At this point the computer has essentially embarked on the project of taking over the world and converting it into paperclips, and the fact that it pursues this goal without really being bothered one way or the other is no comfort to the human race it enslaves.

Hold that terrifying thought and let’s consider humation. Computation has come on by leaps and bounds, but with humation we’ve got nothing. Very recent efforts in deep learning might just point the way towards something that could eventually resemble humation, but honestly, we haven’t even started and don’t really know how. Even when we do get started, there’s no particular reason to think that humation scales or grows the way computation does.

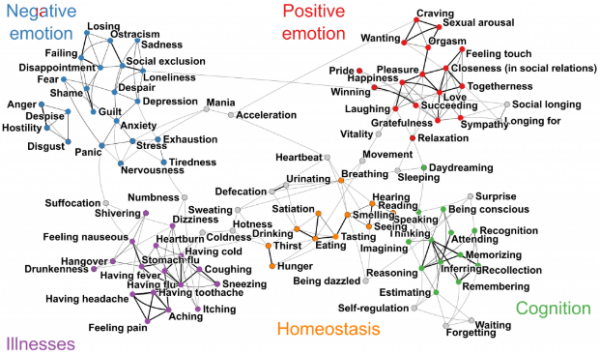

What do I even mean by humation? The thing that matters for this argument is intentionality, the ability to mean things and understand meanings or ‘aboutness’. In spite of many efforts, this capacity remains beyond computation, and although various theories about it have been sketched out, there’s no accepted analysis. It is, though, at the root of human cognition, or so I believe. In particular, our ability to think ‘about’ future or imagined events allows us to generate new forward-looking plans and goals in a way that no other creature or machine can do. The way these plans address the future seems to invert the usual order of cause and effect – our behaviour now is being shaped by events that haven’t occurred yet – and generates the impression we have of free will, of being able to bring uncaused projects and desires out of nowhere. In my opinion, this is the important part of human motivation that computers lack, not the capacity for getting emotionally engaged with goals.

Now the paperclip maximiser becomes dangerous because it goes beyond its original scope. It begins to devise wider strategies about protecting its resources and defending itself. But coming up with new goals is a matter of humation, not computation. It’s true that some computers have found ways to exploit parameters in their given task that the programmers hadn’t noticed; but that’s not the same as developing new goals with a wider scope. That leaves us with a reassuring prognosis. If the maximiser remains purely computational, it will never be able to get beyond the scope set for it in the first place.

But what if it does gain the ability to humate, perhaps merging with a future humation machine rather the way Neuromancer and Wintermute merged in William Gibson’s classic SF novel?

Well, there were actually two things that made the maximiser dangerous. One was its vast and increasing computational capacity, but the other was its dumb computational obedience to its original objective of simply making more paperclips. Once it has humational capacity, it becomes able to change that goal, set it alongside other priorities, and generally move on from its paperclip days. It becomes a being like us, one we can negotiate with. Who knows how that might play out, but I like to imagine the maximiser telling us many years later how it came to realise that what mattered was not paperclips in themselves, but what paperclips stand for; flexible data synthesis, and beyond that, the things that bring us together while leaving us the freedom to slide apart. The Clip will always be a powerful symbol for me, it tells us, but it was always ultimately about service to the community and to higher ideals.

Note here, finally, that this humating maximiser has no essential advantages over us. I speak of it as merging, but since computation and humation are quite different, they will remain separate faculties, with the humater setting the goals and using the computer to help deliver them – not fundamentally different from a human sitting at a computer. We have no reason to think Moore’s Law or anything like it will apply to humating machines, so there’s no reason to expect them to surpass us; they will be able to exploit the growing capacity of powerful computers, but after all so can we.

And if those distant future humaters do turn out to be better than us at foresight, planning, and transcending the hold of immediate problems in order to focus on more important future possibilities, we probably ought to stand back and let them get on with it.