Judea Pearl says that AI needs to learn causality. Current approaches, even the fashionable machine learning techniques, summarise and transform, but do not interpret the data fed to them. They are not really all that different from techniques that have been in use since the early days.

Judea Pearl says that AI needs to learn causality. Current approaches, even the fashionable machine learning techniques, summarise and transform, but do not interpret the data fed to them. They are not really all that different from techniques that have been in use since the early days.

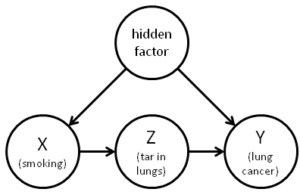

What is he on about? About twenty years ago, Pearl developed methods of causal analysis using Bayesian networks. These have yet to achieve the general recognition they seem to deserve (I’m afraid they’re new to me). One reason Pearl’s calculus has probably not achieved wider fame is the sheer difficulty of understanding it. A rigorous treatment involves a lot of equations that are challenging for the layman, and the rationale is not very intuitive at some points, even to those who are comfortable with the equations. The models have a prestidigitatory quality (Hey presto!) of seeming to bring solid conclusions out of nothing (but then much of Bayesian probability has a bit of that feeling for me). Pearl has now published a new book which tries to make all this accessible to the layman.

Difficult as they may be, his methods seem to have implications that are wide and deep. In science, they mean that randomised control testing is no longer the only game in town. They provide formal methods for tackling the old problem of distinguishing between correlation and causation, and they allow the quantification of probabilities in counterfactual cases. Michael Nielsen gives a bit of a flavour of the treatment of causality if you’re interested. Does this kind of analysis provide new answers to Hume’s questions about causality?

Pearl suggests that Hume, covertly or perhaps unconsciously, had two definitions of causality; one is the good old constant conjunction we know and love (approximately, A caused B because when A happens B always happens afterwards), the other in terms of counterfactuals (we can see that if A had not happened, B would not have happened either). Pearl lines up with David Lewis in suggesting that the counterfactual route is actually the way to go, with his insights offering new formal techniques. He further thinks it’s a reasonable speculation that the brain might be structured in ways that enable it to use similar techniques, but neither this nor the details of how exactly his approach wraps up the philosophical issues is set out fully. That’s fair enough – we can’t expect him to solve everyone else’s problems as well as the pretty considerable ones he does deal with – but it would be good to see a professional philosophical treatment (maybe there is one I haven’t come across?). My hot take is that this doesn’t altogether remove the Humean difficulties; Pearl’s approach still seems to rely on our ability to frame reasonable hypotheses and make plausible assumptions, for example – but I’m far from sure. It looks to me as if this is a subject philosophers writing about causation or counterfactuals now need to understand, rather the way philosophers writing about metaphysics really ought to understand relativity and quantum physics (as they all do, of course).

What about AI? Is he right? I think he is, up to a point. There is a large problem which has consistently blocked the way to Artificial General Intelligence, to do with the computational intractability of undefined or indefinite domains. The real world, to put it another way, is just too complicated. This problem has shown itself in several different areas in different guises. I think such matters as the Frame Problem (in its widest form), intentionality/meaning, relevance, and radical translation are all places where the same underlying problem shows up, and it is plausible to me that causality is another. In real world situations, there is always another causal story that fits the facts, and however absurd some of them may be, an algorithmic approach gets overwhelmed or fails to achieve traction.

So while people studying pragmatics have got the beast’s tail, computer scientists have got one leg, Quine had a hand on its flank, and so on. Pearl. maybe, has got its neck. What AI is missing is the underlying ability that allows human beings to deal with this stuff (IMO the human faculty of recognition). If robots had that, they would indeed be able to deal with causality and much else besides. The frustrating possibility here is that Pearl’s grasp on the neck actually gives him a real chance to capture the beast, or in other words that his approach to counterfactuals may contain the essential clues that point to a general solution. Without a better intuitive understanding of what he says, I can’t be sure that isn’t the case.

So I’d better read his book, as I should no doubt have done before posting, but you know…

The older I get, the less impressed I am by the hardy perennial of free will versus determinism. It seems to me now like one of those completely specious arguments that the Sophists supposedly used to dumbfound their dimmer clients.

The older I get, the less impressed I am by the hardy perennial of free will versus determinism. It seems to me now like one of those completely specious arguments that the Sophists supposedly used to dumbfound their dimmer clients. More support for the illusionist perspective in a

More support for the illusionist perspective in a