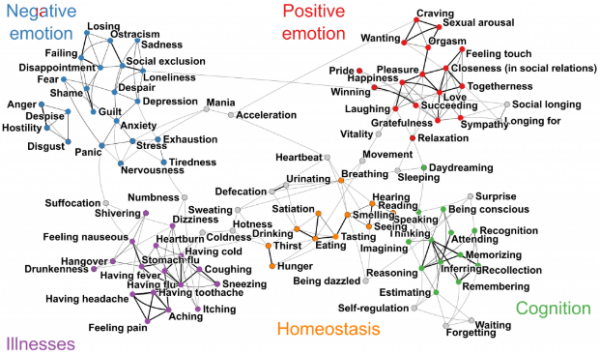

An intriguing study by Nummenmaa et al (paper here) offers us a new map of human feelings, which it groups into five main areas; positive emotions, negative emotions, cognitive operations, homeostatic functions, and sensations of illness. The hundred feelings used to map the territory are all associated with physical regions of the human body.

The map itself is mostly rather interesting and the five groups seem to make broad sense, though a superficial look also reveals a few apparent oddities. ‘Wanting’ here is close to ‘orgasm’. For some years now I’ve wanted to clarify the nature of consciousness; writing this blog has been fun, but dear reader, never quite like that. I suppose ‘wanting’ is being read as mainly a matter of biological appetites, but the desire and its fulfilment still seem pretty distinct to me, even on that reading.

Generally, a list of methodological worries come to mind, many of which are connected with the notorious difficulties of introspective research. ‘Feelings’ is a rather vaguely inclusive word, to begin with. There are a number of different approaches to classifying the emotions already available, but I have not previously encountered an attempt to go wider for a comprehensive coverage of every kind of feeling. It seems natural to worry that ‘feelings’ in this broad sense might in fact be a heterogeneous grouping, more like several distinct areas bolted together by an accident of language; it certainly feels strange to see thinking and urination, say, presented as members of the same extended family. But why not?

The research seems to rest mainly on responses from a group of more than 1000 subjects, though the paper also mentions drawing on the NeuroSynth meta-analysis database in order to look at neural similarity. The study imported some assumptions by using a list of 100 feelings, and by using four hypothesized basic dimensions – mental experience, bodily sensation, emotion, and controllability. It’s possible that some of the final structure of the map reflects these assumptions to a degree. But it’s legitimate to put forward hypotheses, and that perhaps need not worry us too much so long as the results seem consistent and illuminating. I’m a little less comfortable with the notion here of ‘similarity’; subjects were asked to put feelings closer the more similar they felt them to be, in two dimensions. I suspect that similarity could be read in various ways, and the results might be very vulnerable to priming and contextual effects.

Probably the least palatable aspect, though, is the part of the study relating feelings to body regions. Respondents were asked to say where they felt each of the feelings, with ‘nowhere’, ‘out there’ or ‘in Platonic space’ not being admissible responses. No surprises about where urination was felt, nor, I suppose, about the fact that the cognitive stuff was considered to be all in the head. But the idea that thinking is simply a brain function is philosophically controversial, under attack from, among others, those who say ‘meaning ain’t in the head’, those who champion the extended brain (if you’re counting on your fingers, are you still thinking with just your brain?), those who warn us against the ‘mereological fallacy’, and those like our old friend Riccardo Manzotti, who keeps trying to get us to understand that consciousness is external.

Of course it depends what kind of claim these results might be intended to ground. As a study of ‘folk’ psychology, they would be unobjectionable, but we are bound to suspect that they might be called in support of a reductive theory. The reductive idea that feelings are ultimately nothing more than bodily sensations is a respectable one with a pedigree going back to William James and beyond; but in the context of claims like that a study that simply asks subjects to mark up on a diagram of the body where feelings happen is begging some questions.